Walpole, Horace, The Castle of Otranto: A Story. 1764

Rating: 7/10

The Castle of Otranto at Goodreads

The Castle of Otranto at ISFdb

The Castle of Otranto at IBList

For other Friday's Forgotten Books, this week please visit B.V. Lawson's in reference to murder.

During the latter era of the Crusades, Prince Manfred, overseer of Otranto, is profoundly shaken when his sickly son and only heir is killed by an over-sized helmet on the morning of his betrothal to the beautiful Isabella. Alas, the curse of Manfred appears to be coming to fruition, vengeance against his lineage that had unlawfully taken ownership of the region and castle of Otranto. Soon thereafter heroic peasants, ominous knights, comedic servants and colossal spectres abound at the castle while Manfred attempts to salvage his lineage via some vulgar attachments.

During the latter era of the Crusades, Prince Manfred, overseer of Otranto, is profoundly shaken when his sickly son and only heir is killed by an over-sized helmet on the morning of his betrothal to the beautiful Isabella. Alas, the curse of Manfred appears to be coming to fruition, vengeance against his lineage that had unlawfully taken ownership of the region and castle of Otranto. Soon thereafter heroic peasants, ominous knights, comedic servants and colossal spectres abound at the castle while Manfred attempts to salvage his lineage via some vulgar attachments.

A great deal has been written about this little novel, from the elements that help establish Gothic fiction to its historical context, and much of the criticism and historical evaluation of The Castle of Otranto is fascinating. Walpole chose to publish the text under the pseudonym William Marshal, and went to great lengths to convince the public that Marshal was merely translating a recently discovered manuscript by the (fictional) Italian Onuphrio Muralto from the early medieval era. Critics were fascinated by the translation and the work itself, and the book sold well, so that Walpole admitted to its authorship, resulting in critics panning the book for its overly melodramatic style and its purely Romantic approach. Readers, however, continued to be entertained.

The novel is marred for modern readers due to its incredible level of melodrama and the sudden reveal of information, a kind of deus ex machina, that exposes secrets unknown to the reader and most characters, information withheld, that brings the plot to its conclusion. With patience, however, the novel is enjoyable partly because of its melodrama, and though the prose is uneven, the ambitious use of language is often unique and a treat to the linguistic portions of our brains. Taken tongue-in-cheek of course, the nearly absurdist humour continues to be effective, though the villain Manfred is at these moments comical himself in his frustrations, diminishing his status as über melodramatic bad guy. The intense melodrama and wild humour make for an unusual mix, yet help to raise the novel above the weights of darkness and gloom that otherwise drag after steady, uninterrupted reading.

Despite its positive and eccentric elements, The Castle of Otranto remains consistently reputed as a terribly dull work that launched an incredibly rich and lucrative literary and eventual film (sub)genre. The novel's quasi-historical elements, broad yet ruinous landscapes, gloomy themes and tone, powerful characters and emotions, not to mention the requisite appearance of a ghost, helped to enliven imaginations of the later Victorians who themselves propelled the literary Gothic forward into the twentieth century. Since then film has broadened its scope so that the Gothic appears a full-fledged genre of its known. The seventeenth century Gothic borrowed from medieval history and poetry, whereas current Gothic fiction borrows heavily from the eighteenth century, reminding us of just how long the genre has been striving, since while it borrows heavily from the past, the contemporary form finds itself attached to a century beyond the genre's initial works.

What I liked about The Castle of Otranto as a novel rather than a literary artifact is the mysterious giant phantom whose body parts appear at different parts of the castle. Truly creepy to this day, its effect weakened by the comedy surrounding servants trying to explain their sight of it. The idea of two leaders planning to marry each other's daughters in order to guarantee that each has an heir to their respective kingdoms is both interesting and sickening, controversial even in its day. We have a medieval priest who fathered a son, and two princess heroines who love the same heroic peasant. Walpole wrote in a later edition preface that he was attempting to combine elements of both traditional and contemporary romance. I believe the intention since the book has elements of traditional chivalric romance along the lines of The Romance of the Rose, mixed in with quite modern ideas, like the hero who settles for the woman he does not love since she understands his grief over the woman he has lost and cannot stop loving. Life even for our heroes holds misery, a far removal from notions of classic romance.

The Castle of Otranto is not a book I would recommend to the casual reader, nor to the canon of western literature. It is a fascinating and important literary artifact, but not necessarily a good book. Anyone wishing to trace the evolution of English literature, or to even grasp certain threads that bind contemporary mainstream fiction to the past, would benefit with a close read. Anyone wanting an entertaining summer read, classic or otherwise, has numerous superior options.

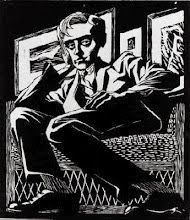

Not only an interesting postmodern film, a false documentary of a false history, but The Castle of Otranto was adapted into a short comic. Less an adaptation but a kind of interpretation, dropping and exchanging some major story elements, and they managed to get the publication date wrong. You can read the comic here.

Rating: 7/10

The Castle of Otranto at Goodreads

The Castle of Otranto at ISFdb

The Castle of Otranto at IBList

For other Friday's Forgotten Books, this week please visit B.V. Lawson's in reference to murder.

During the latter era of the Crusades, Prince Manfred, overseer of Otranto, is profoundly shaken when his sickly son and only heir is killed by an over-sized helmet on the morning of his betrothal to the beautiful Isabella. Alas, the curse of Manfred appears to be coming to fruition, vengeance against his lineage that had unlawfully taken ownership of the region and castle of Otranto. Soon thereafter heroic peasants, ominous knights, comedic servants and colossal spectres abound at the castle while Manfred attempts to salvage his lineage via some vulgar attachments.

During the latter era of the Crusades, Prince Manfred, overseer of Otranto, is profoundly shaken when his sickly son and only heir is killed by an over-sized helmet on the morning of his betrothal to the beautiful Isabella. Alas, the curse of Manfred appears to be coming to fruition, vengeance against his lineage that had unlawfully taken ownership of the region and castle of Otranto. Soon thereafter heroic peasants, ominous knights, comedic servants and colossal spectres abound at the castle while Manfred attempts to salvage his lineage via some vulgar attachments.A great deal has been written about this little novel, from the elements that help establish Gothic fiction to its historical context, and much of the criticism and historical evaluation of The Castle of Otranto is fascinating. Walpole chose to publish the text under the pseudonym William Marshal, and went to great lengths to convince the public that Marshal was merely translating a recently discovered manuscript by the (fictional) Italian Onuphrio Muralto from the early medieval era. Critics were fascinated by the translation and the work itself, and the book sold well, so that Walpole admitted to its authorship, resulting in critics panning the book for its overly melodramatic style and its purely Romantic approach. Readers, however, continued to be entertained.

The novel is marred for modern readers due to its incredible level of melodrama and the sudden reveal of information, a kind of deus ex machina, that exposes secrets unknown to the reader and most characters, information withheld, that brings the plot to its conclusion. With patience, however, the novel is enjoyable partly because of its melodrama, and though the prose is uneven, the ambitious use of language is often unique and a treat to the linguistic portions of our brains. Taken tongue-in-cheek of course, the nearly absurdist humour continues to be effective, though the villain Manfred is at these moments comical himself in his frustrations, diminishing his status as über melodramatic bad guy. The intense melodrama and wild humour make for an unusual mix, yet help to raise the novel above the weights of darkness and gloom that otherwise drag after steady, uninterrupted reading.

Despite its positive and eccentric elements, The Castle of Otranto remains consistently reputed as a terribly dull work that launched an incredibly rich and lucrative literary and eventual film (sub)genre. The novel's quasi-historical elements, broad yet ruinous landscapes, gloomy themes and tone, powerful characters and emotions, not to mention the requisite appearance of a ghost, helped to enliven imaginations of the later Victorians who themselves propelled the literary Gothic forward into the twentieth century. Since then film has broadened its scope so that the Gothic appears a full-fledged genre of its known. The seventeenth century Gothic borrowed from medieval history and poetry, whereas current Gothic fiction borrows heavily from the eighteenth century, reminding us of just how long the genre has been striving, since while it borrows heavily from the past, the contemporary form finds itself attached to a century beyond the genre's initial works.

What I liked about The Castle of Otranto as a novel rather than a literary artifact is the mysterious giant phantom whose body parts appear at different parts of the castle. Truly creepy to this day, its effect weakened by the comedy surrounding servants trying to explain their sight of it. The idea of two leaders planning to marry each other's daughters in order to guarantee that each has an heir to their respective kingdoms is both interesting and sickening, controversial even in its day. We have a medieval priest who fathered a son, and two princess heroines who love the same heroic peasant. Walpole wrote in a later edition preface that he was attempting to combine elements of both traditional and contemporary romance. I believe the intention since the book has elements of traditional chivalric romance along the lines of The Romance of the Rose, mixed in with quite modern ideas, like the hero who settles for the woman he does not love since she understands his grief over the woman he has lost and cannot stop loving. Life even for our heroes holds misery, a far removal from notions of classic romance.

The Castle of Otranto is not a book I would recommend to the casual reader, nor to the canon of western literature. It is a fascinating and important literary artifact, but not necessarily a good book. Anyone wishing to trace the evolution of English literature, or to even grasp certain threads that bind contemporary mainstream fiction to the past, would benefit with a close read. Anyone wanting an entertaining summer read, classic or otherwise, has numerous superior options.

|

| A scene from the 1979 short film by Jan Švankmajer |