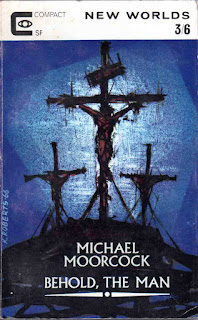

Moorcock, Michael. "Behold the Man." New Worlds SF, September 1966.

This article is part of my attempt to read the 155 stories currently (as of 1 November 2022) on the ISFdb's Top Short Fiction list. Please see the introduction and list of stories here. I am encouraging readers to rate the stories and books they have read on the ISFdb.

ISFdb Rating: 9.33/10

My Rating: 9/10

"The time machine was a sphere full of milky fluid in which the traveller floated, enclosed in a rubber suit, breathing through a mask attached to a hose leading to the wall of the machine."

(I was gonna to cheat & not re-read this one. I've read the novella & the novel versions multiple times when I was younger. While I've also read the lengthy "Flowers for Algernon" multiple times, I was happy to re-visit it anew for this project. With "Behold the Man," I just wasn't in the mood and thought I'd be too bored for the fifty-page slog. Unlike Keyes's story, I didn't expect to return to it soon, if ever. While I've always liked it, I do feel I've grown a little tired of this one, and my last re-read about a decade ago did find me less immersed. I believe it has to do with the unsympathetic protagonist. However, I looked up an e-version of the New Worlds issue in which it first appeared, & was hooked with the first sentence.)

Karl Glogauer is a young and whiney pseudo-intellectual with little drive, or at least little healthy drive. Stuck in a bad relationship and running a bookshop bought from an inheritance, a business in which he does not appear interested, Glogauer is in the search for some kind of meaning in his life. He appears motivated by the constant fights he has with his older cynical girlfriend psychiatrist Monica, and decides he would love to prove that Jesus Christ did exist, and however corrupt the religion may come in the last two centuries, that there is at least a base minimal truth at its inception. It is not the religion, however, he is concerned about, or historical accuracy or the base of much of western culture; he wants to prove Monica wrong. Really, this kind of vindictiveness-fueled purpose does not garner much sympathy, and it is difficult to care for either his or Monica's world views.

Yet it is just these kinds of characters that can trigger such an off-the-wall journey. As part of a Jungian reading circle organized at his bookshop, Glogauer meets a man who claims to have built a time machine, and wants Karl to be the test pilot. Glogauer of course agrees, so long as he can decide the destination in both time and space.

The journey for Christ is what makes the story so interesting, as Moorcock manages to re-create the world that might have been. His depiction of John the Baptist and his community of Essenes are probably the most interesting parts of the novella. John's conversations with Karl are not only interesting in themselves, but offer a nice contrast with Karl's conversation with Monica. There is genuine humanity and concern here, as though Karl does belong in the past, or perhaps modern human interaction, even in dialogue, has become destructive.

Because it is Moorcock, the reality we expect is turned upside down. While John the Baptist as an Essene is believable and creates a very real image of biblical writing, rather than the quietly charismatic leader popular culture has come to expect from Jesus Christ, he is instead an idiot child. He lives with his struggling parents who do not dote on him, but openly show their distaste for him. Glogauer is utterly shocked, whether by the reality of what he is experiencing, or because he cannot prove cold-hearted Monica's arguments to be at fault, and after some delusional episodes, decides that he must realize (resurrect?) the historical Christ, and sets off, still semi delusional, to become that man.

Truly fascinating, well presented and nicely structured as it leaps from one point in time to another, a conversation here to one over there... And with a great ending which, to me, seals Karl's failure, though this can be argued.

As for what is better, the novella or novel... I haven't re-read the novel version in many years and don't feel I need to. The novel spends more time on Karl's childhood, on sexual abuse at the hands of the church, while also exaggerating much of the extreme portions of the novella, such as the idiot child Jesus, and the less-than-Virgin Mary. I do not think these elements add to the story. I am not offended by any of them, though an atheist who is highly respectful of all religion, I just feel the exaggeration is unnecessary. Moorcock proves his point in the novella, and overkills it in the novel. The story is not about Christianity or how much truth there is in the biblical stories, but it is more about the lost youth of 1960s-70s England, who is without purpose and chooses to carve a meaningless objective for their lives, in this case to spite a lover.

No comments:

Post a Comment