Casual Debris has evolved a little from its inception. Currently, we are interested in anthologies, literary and genre, as well as television. We also like to review lesser known novels and stories, and toss in a few asides, now and again. Thank you for stopping by.

Casual Dedris Presents:

Tuesday, November 29, 2022

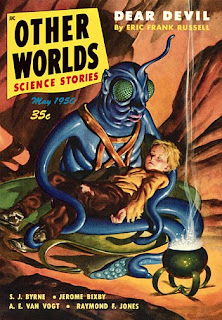

Casual Shorts & the ISFdb Top Short Fiction #6: Dear Devil by Eric Frank Russell

Friday, November 25, 2022

Casual Shorts & the ISFdb Top Short Fiction #5: The Screwfly Solution by James Tiptree Jr

Tiptree, Jr., James. "The Screwfly Solution." Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, June 1977.

Thursday, November 17, 2022

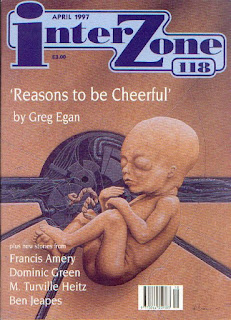

Casual Shorts & the ISFdb Top Short Fiction #4: Reasons to Be Cheerful by Greg Egan

Egan, Greg. "Reasons to Be Cheerful." Interzone #118, April 1997.

Friday, November 11, 2022

Casual Shorts & the ISFdb Top Short Fiction #3: It's a Good Life by Jerome Bixby

Monday, November 7, 2022

Casual Shorts & the ISFdb Top Short Fiction #2: Nightmare at 20,000 Feet by Richard Matheson

Friday, November 4, 2022

Casual Shorts & the ISFdb Top Short Fiction #1: Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes

Tuesday, November 1, 2022

Project: ISFdb Top Short Fiction

|

Rank |

Rating |

Title |

Year |

Author(s) |

|

1 |

9.79 |

1959 |

Daniel Keyes |

|

|

2 |

9.67 |

1962 |

Richard Matheson |

|

|

3 |

9.67 |

1953 |

Jerome Bixby |

|

|

4 |

9.67 |

1997 |

Greg Egan |

|

|

5 |

9.5 |

1977 |

James Tiptree, Jr. |

|

|

6 |

9.5 |

1950 |

Eric Frank Russell |

|

|

7 |

9.38 |

1973 |

James Tiptree, Jr. |

|

|

8 |

9.33 |

1843 |

Edgar Allan Poe |

|

|

9 |

9.33 |

1966 |

Michael Moorcock |

|

|

10 |

9.3 |

1936 |

H. P. Lovecraft |

|

|

11 |

9.18 |

1977 |

Harlan Ellison |

|

|

12 |

9.17 |

1998 |

Ted Chiang |

|

|

13 |

9.14 |

1963 |

Roger Zelazny |

|

|

14 |

9.14 |

1956 |

Isaac Asimov |

|

|

15 |

9.14 |

1950 |

Cordwainer Smith |

|

|

16 |

9.14 |

1966 |

Bob Shaw |

|

|

17 |

9.12 |

1950 |

C. M. Kornbluth |

|

|

18 |

9.11 |

1954 |

Alfred Bester |

|

|

19 |

9.08 |

1943 |

Lewis Padgett |

|

|

20 |

9.08 |

1928 |

H. P. Lovecraft |

|

|

21 |

9.06 |

1941 |

Isaac Asimov |

|

|

22 |

9.00 |

1842 |

Edgar Allan Poe |

|

|

23 |

9.00 |

1843 |

Edgar Allan Poe |

|

|

24 |

9.00 |

1846 |

Edgar Allan Poe |

|

|

25 |

9.00 |

1909 |

E. M. Forster |

|

|

26 |

9.00 |

1979 |

Barry B. Longyear |

|

|

27 |

9.00 |

1949 |

Ray Bradbury |

|

|

28 |

8.93 |

1973 |

Ursula K. Le Guin |

|

|

29 |

8.91 |

1952 |

Ray Bradbury |

|

|

30 |

8.9 |

1972 |

Ursula K. Le Guin |

|

|

31 |

8.88 |

1979 |

George R. R. Martin |

|

|

32 |

8.88 |

1953 |

Philip K. Dick |

|

|

33 |

8.86 |

1951 |

C. M. Kornbluth |

|

|

34 |

8.86 |

1951 |

Anthony Boucher |

|

|

35 |

8.83 |

1981 |

William Gibson |

|

|

36 |

8.83 |

1972 |

James Tiptree, Jr. |

|

|

37 |

8.83 |

1944 |

Fredric Brown |

|

|

38 |

8.83 |

1984 |

Kim Stanley Robinson |

|

|

39 |

8.82 |

1950 |

Ray Bradbury |

|

|

40 |

8.75 |

1902 |

W. W. Jacobs |

|

|

41 |

8.75 |

1929 |

H. P. Lovecraft |

|

|

42 |

8.71 |

1941 |

Robert A. Heinlein |

|

|

43 |

8.71 |

1941 |

Robert A. Heinlein |

|

|

44 |

8.71 |

1953 |

Arthur C. Clarke |

|

|

45 |

8.71 |

1890 |

Ambrose Bierce |

|

|

46 |

8.7 |

1990 |

Ted Chiang |

|

|

47 |

8.7 |

1968 |

Robert Silverberg |

|

|

48 |

8.7 |

1969 |

Harlan Ellison |

|

|

49 |

8.67 |

1944 |

Clifford D. Simak |

|

|

50 |

8.67 |

1953 |

Philip K. Dick |

|

|

51 |

8.67 |

Nightwings |

1968 |

Robert Silverberg |

|

52 |

8.67 |

Sailing to Byzantium |

1985 |

Robert Silverberg |

|

53 |

8.62 |

Foundation |

1942 |

Isaac Asimov |

|

54 |

8.62 |

Hell Is the Absence of God |

2001 |

Ted Chiang |

|

55 |

8.62 |

We Can Remember It for You Wholesale |

1966 |

Philip K. Dick |

|

56 |

8.6 |

When It Changed |

1972 |

Joanna Russ |

|

57 |

8.57 |

The Persistence of Vision |

1978 |

John Varley |

|

58 |

8.55 |

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream |

1967 |

Harlan Ellison |

|

59 |

8.5 |

Fire Watch |

1982 |

Connie Willis |

|

60 |

8.5 |

Houston, Houston, Do You Read? |

1976 |

James Tiptree, Jr. |

|

61 |

8.5 |

The Colour Out of Space |

1927 |

H. P. Lovecraft |

|

62 |

8.5 |

A Martian Odyssey |

1934 |

Stanley G. Weinbaum |

|

63 |

8.5 |

Seventy-Two Letters |

2000 |

Ted Chiang |

|

64 |

8.47 |

The Cold Equations |

1954 |

Tom Godwin |

|

65 |

8.46 |

"All You Zombies ..." |

1959 |

Robert A. Heinlein |

|

66 |

8.44 |

Allamagoosa |

1955 |

Eric Frank Russell |

|

67 |

8.43 |

Blood Music |

1983 |

Greg Bear |

|

68 |

8.43 |

The Ugly Chickens |

1980 |

Howard Waldrop |

|

69 |

8.43 |

Beyond Lies the Wub |

1952 |

Philip K. Dick |

|

70 |

8.43 |

To Serve Man |

1950 |

Damon Knight |

|

71 |

8.33 |

Understand |

1991 |

Ted Chiang |

|

72 |

8.33 |

The Pusher |

1981 |

John Varley |

|

73 |

8.33 |

The Star |

1955 |

Arthur C. Clarke |

|

74 |

8.31 |

Ender's Game |

1977 |

Orson Scott Card |

|

75 |

8.29 |

Speech Sounds |

1983 |

Octavia E. Butler |

|

76 |

8.29 |

The Crystal Egg |

1897 |

H. G. Wells |

|

77 |

8.25 |

Microcosmic God |

1941 |

Theodore Sturgeon |

|

78 |

8.25 |

There Will Come Soft Rains |

1950 |

Ray Bradbury |

|

79 |

8.22 |

Coraline |

2002 |

Neil Gaiman |

|

80 |

8.17 |

The State of the Art |

1989 |

Iain M. Banks |

|

81 |

8.17 |

That Only a Mother |

1948 |

Judith Merril |

|

82 |

8.14 |

That Hell-Bound Train |

1958 |

Robert Bloch |

|

83 |

8.14 |

Neutron Star |

1966 |

Larry Niven |

|

84 |

8.14 |

The Way of Cross and Dragon |

1979 |

George R. R. Martin |

|

85 |

8.14 |

The Bicentennial Man |

1976 |

Isaac Asimov |

|

86 |

8.00 |

The Big Front Yard |

1958 |

Clifford D. Simak |

|

87 |

8.00 |

Love Is the Plan the Plan Is Death |

1973 |

James Tiptree, Jr. |

|

88 |

8.00 |

A Song for Lya |

1974 |

George R. R. Martin |

|

89 |

8.00 |

The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath |

1943 |

H. P. Lovecraft |

|

90 |

8.00 |

The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar |

1845 |

Edgar Allan Poe |

|

91 |

8.00 |

First Contact |

1945 |

Murray Leinster |

|

92 |

7.94 |

"Repent, Harlequin!" Said

the Ticktockman |

1965 |

Harlan Ellison |

|

93 |

7.91 |

The Sentinel |

1951 |

Arthur C. Clarke |

|

94 |

7.89 |

Nine Lives |

1969 |

Ursula K. Le Guin |

|

95 |

7.89 |

The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of

His Mouth |

1965 |

Roger Zelazny |

|

96 |

7.88 |

The Fall of the House of Usher |

1839 |

Edgar Allan Poe |

|

97 |

7.86 |

A Meeting with Medusa |

1971 |

Arthur C. Clarke |

|

98 |

7.86 |

The Monkey Treatment |

1983 |

George R. R. Martin |

|

99 |

7.86 |

The Day Before the Revolution |

1974 |

Ursula K. Le Guin |

|

100 |

7.85 |

Press Enter ▮? |

1984 |

John Varley |

|

101 |

7.83 |

Rescue Party |

1946 |

Arthur C. Clarke |

|

102 |

7.83 |

Earthmen Bearing Gifts |

1960 |

Fredric Brown |

|

103 |

7.83 |

Air Raid |

1977 |

John Varley |

|

104 |

7.8 |

Nightflyers |

1980 |

George R. R. Martin |

|

105 |

7.75 |

The Rats in the Walls |

1924 |

H. P. Lovecraft |

|

106 |

7.67 |

Liar! |

1941 |

Isaac Asimov |

|

107 |

7.67 |

The Green Hills of Earth |

1947 |

Robert A. Heinlein |

|

108 |

7.58 |

Born of Man and Woman |

1950 |

Richard Matheson |

|

109 |

7.57 |

Super-Toys Last All Summer Long |

1969 |

Brian W. Aldiss |

|

110 |

7.57 |

Shambleau |

1933 |

C. L. Moore |

|

111 |

7.56 |

Bloodchild |

1984 |

Octavia E. Butler |

|

112 |

7.56 |

The Fog Horn |

1951 |

Ray Bradbury |

|

113 |

7.56 |

The New Accelerator |

1901 |

H. G. Wells |

|

114 |

7.56 |

Third from the Sun |

1950 |

Richard Matheson |

|

115 |

7.5 |

Bears Discover Fire |

1990 |

Terry Bisson |

|

116 |

7.5 |

Requiem |

1940 |

Robert A. Heinlein |

|

117 |

7.5 |

Grotto of the Dancing Deer |

1980 |

Clifford D. Simak |

|

118 |

7.5 |

Call Him Lord |

1966 |

Gordon R. Dickson |

|

119 |

7.44 |

The Deathbird |

1973 |

Harlan Ellison |

|

120 |

7.43 |

Dagon |

1919 |

H. P. Lovecraft |

|

121 |

7.42 |

The Roads Must Roll |

1940 |

Robert A. Heinlein |

|

122 |

7.4 |

Gonna Roll the Bones |

1967 |

Fritz Leiber |

|

123 |

7.38 |

The Star |

1897 |

H. G. Wells |

|

124 |

7.33 |

Out of All Them Bright Stars |

1985 |

Nancy Kress |

|

125 |

7.33 |

Vaster Than Empires and More Slow |

1971 |

Ursula K. Le Guin |

|

126 |

7.33 |

Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand |

1973 |

Vonda N. McIntyre |

|

127 |

7.29 |

Or All the Seas with Oysters |

1958 |

Avram Davidson |

|

128 |

7.29 |

26 Monkeys, Also the Abyss |

2008 |

Kij Johnson |

|

129 |

7.25 |

Helen O'Loy |

1938 |

Lester del Rey |

|

130 |

7.25 |

Life-Line |

1939 |

Robert A. Heinlein |

|

131 |

7.17 |

The Whimper of Whipped Dogs |

1973 |

Harlan Ellison |

|

132 |

7.17 |

Roog |

1953 |

Philip K. Dick |

|

133 |

7.17 |

Division by Zero |

1991 |

Ted Chiang |

|

134 |

7.17 |

A Subway Named Mobius |

1950 |

A. J. Deutsch |

|

135 |

7.14 |

The Father-Thing |

1954 |

Philip K. Dick |

|

136 |

7.14 |

Reason |

1941 |

Isaac Asimov |

|

137 |

7.12 |

The Weapon Shop |

1942 |

A. E. van Vogt |

|

138 |

7.12 |

Runaround |

1942 |

Isaac Asimov |

|

139 |

7.00 |

Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes |

1967 |

Harlan Ellison |

|

140 |

7.00 |

Grandpa |

1955 |

James H. Schmitz |

|

141 |

7.00 |

Coming Attraction |

1950 |

Fritz Leiber |

|

142 |

7.00 |

The Monsters |

1953 |

Robert Sheckley |

|

143 |

7.00 |

Meathouse Man |

1976 |

George R. R. Martin |

|

144 |

7.00 |

He Who Shapes |

1965 |

Roger Zelazny |

|

145 |

6.89 |

Aye, and Gomorrah ... |

1967 |

Samuel R. Delany |

|

146 |

6.86 |

Dinner in Audoghast |

1985 |

Bruce Sterling |

|

147 |

6.83 |

Slow Sculpture |

1970 |

Theodore Sturgeon |

|

148 |

6.83 |

Strange Playfellow |

1940 |

Isaac Asimov |

|

149 |

6.57 |

Good News from the Vatican |

1971 |

Robert Silverberg |

|

150 |

6.55 |

Time Considered as a Helix of

Semi-Precious Stones |

1968 |

Samuel R. Delany |

|

151 |

6.33 |

Fermi and Frost |

1985 |

Frederik Pohl |

|

152 |

6.33 |

The Man Who Could Work Miracles |

1898 |

H. G. Wells |

|

153 |

6.17 |

The Hole Man |

1974 |

Larry Niven |

|

154 |

6.17 |

Blowups Happen |

1940 |

Robert A. Heinlein |

|

155 |

5.5 |

Adrift Just Off the Islets of

Langerhans: Latitude 38° 54' N, Longitude 77° 00' 13" W |

1974 |

Harlan Ellison |