Matheson, Richard. "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet." Alone By Night, Don Congdon & Michael Congdon, eds. New York: Ballantine Books, January 1962.

This article is part of my attempt to read the 155 stories currently (as of 1 November 2022) on the ISFdb's Top Short Fiction list. Please see the introduction and list of stories here. I am encouraging readers to rate the stories and books they have read on the ISFdb.

ISFdb Rating: 9.67/10

My Rating: 9/10

"Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" is tied with Jerome Bixby's "It's a Good Life" (1953) and Greg Egan's "Reasons to Be Cheerful" (1997).

"'Seat belt, please.' said the stewardess cheerfully as she passed him."

Businessman Arthur Jeffrey Wilson is riding on a DC-7 to meet with a client. Wilson would prefer not being on the trip, or at least to be travelling by train: he is a bitter, cynical and anxiety-ridden man, with a fear of flying. Moreover, he carries a gun with him claiming to do so for self-defense, yet it is implied he has suicidal tendencies. He has even brought it aboard this flight. His fear of flying has led Wilson to book a seat by the emergency door, from where he also has a clear view of the plane's wing. Shortly into the flight, he sees a man on the wing of the plane. Not a man, on closer inspection, but a hideous "gremlin" who appears to be sabotaging the engine. Unfortunately, no one else can see the creature, and Wilson is convinced he is not hallucinating.

Over his lengthy writing career, Matheson has come up with some great story premises. This one is, truthfully, quite silly: a gremlin balancing on the wing of a plane. The story, however, is expertly constructed, and the focus is primarily on the protagonist, his overall character and reaction to the odd event, leaving the creature little more than incidental, or a device to bring out the worst in Wilson. We are introduced quickly to the setting and its protagonist, and a few paragraphs give us what we need to now about Wilson: a weak, seemingly disillusioned and anxious businessman. Moreover, he is less than sober, medicated with Dramamine and sleeping pills. Normally, in a story dealing with a person who witnesses something unlikely, we sympathize with that person, believing that their experiences are real regardless of the disbelieving entourage. Yet in this story we are uncertain, and it often appears that the greatest threat to the plane is the gun-wielding Wilson, and not the supposed gremlin.

The best aspect of the story is that there is no objective resolution, and we can interpret the "gremlin" and its existence in many ways. Perhaps a manifestation of Wilson's anxiety-filled and drug-induced mind, a kind of "pink elephant." It may be a hallucination brought on by a life less-than-fulfilled, as he remarks that his work, this trip and in essence his purpose in life, has little meaning, and what he does will have no significance on the history of humankind, as he puts it. Or maybe the creature is all-too real, as Wilson recalls the articles he's read of creatures attacking military planes during World War II, so that there is some objective, albeit flimsy, evidence.

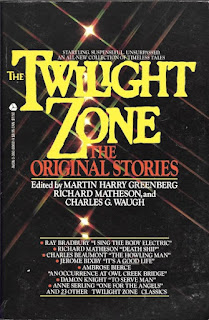

Matheson's excellent, ambiguous and suspense-filled short story is best known for its Twilight Zone adaptations. First in 1963, the year following the story's original publication. This episode is considered the strongest of a weak fifth season, as well as among the strongest of the entire series (the second of two TZ episodes to feature future Captain Kirk, William Shatner). The second adaptation was the high-point of the 1983 Twilight Zone: The Movie, a segment directed by George Miller and with a brilliant performance by John Lithgow. Both screenplays were written by Matheson, but the one for the movie retains the ambiguity, whereas the TV episode gives us external evidence that the creature did exist. I'm pretty sure I first read the short story in the 1985 anthology The Twilight Zone: The Original Stories (Martin Harry Greenberg, Richard Matheson & Charles G. Waugh, eds., Avon Books, July 1985), which I purchased in 1986. The story is not among his most anthologized, oddly less so than many a weaker piece, but remains in my opinion among his strongest.

For a concise bibliography, please visit the story's ISFdb page.

No comments:

Post a Comment