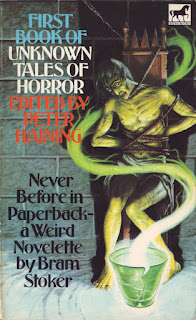

Haining, Peter, ed. The First Book of Unknown Tales of Terror. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, June 1976.

______. The First Book of Unknown Tales of Terror. London: Mews Books, October 1976. (pictured)

The First Book of Unknown Tales of Terror at the ISFdb The First Book of Unknown Tales of Terror at Goodreads

Overall Rating: 6/10

|

| Mews Books, 1976 |

This small collection is part of a series of three books assembled by prolific anthologist Peter Haining, collecting little known works from a combination of popular and lesser known supernatural fiction authors. Haining writes in his introduction that there has been an inundation of horror anthologies in recent years (1976), and that the same stories are being reprinted repeatedly, and that "the endlessly patient readership has accepted this in the hope, too often vain, that amongst the familiar there might occasionally appear the unfamiliar."

The idea is a good one, and yet there is usually a reason most neglected stories have not been often reprinted, and that is mainly because they are not very good. Had they been of better quality, they would not have been neglected, or published/re-printed only long after the author's death (as is the case with the Bram Stoker and Robert E. Howard stories). The anthology is, however, far better than I expected it to be. While it is not brilliant, it does include some stories I am happy to have read. It is of interest primarily to those who generally enjoy supernatural tales, but a casual reader would likely not care for most of what Haining has put together. The stories are not bad by any means, though there are a couple of weak ones included. My favourite is the first, H. Russell Wakefield's "The Sepulchre of Jasper Sarasen," while I also enjoyed the Arthur Machen story, "The Cosy Room," and the next-to-last story, which has no supernatural element but some good writing and fine suspense, Francis Clifford's "Ten Minutes on a June Morning."

The Sepulchre of Jasper Sarasen by H. Russell Wakefield 7/10

Fantastic Universe, August/September 1953

Ornithologist Sir Reginald Ramley comes across a sepulchre containing six coffins. The burial grounds are decrepit, likely the result of a bomb from the recent war. Speaking with the cemetery warden, Ramley learns that the coffins belong to a woman and four children, and the husband/father who is believed to have murdered them, and who died mysteriously shortly afterwards. For some odd reason, Ramley is drawn to the coffins, dreaming of the sepulchre and when awake, feeling drawn to return.

Very much a Victorian ghost story in style and tone, the story is quite engaging and creepy,

The Crystal Cup by Bram Stoker 6/10

London Society, September 1872

An artist captured and imprisoned so that he creates a thing of beauty for the upcoming Feast of Beauty, suffers and pines for his lost love. He builds a splendid crystal cup, and dies. The Feast of Beauty is held, and revenge, as expected, is meted out. Split into three sections with three points of view, the story is interesting enough, but for the melodramatic over-writing of the first and third sections. In the introduction Haining mentions the story has not yet been collected, and it is likely because it is not very good. Not Stoker's best work by a long shot, but there is evidence of talent in this early story.

The Cosy Room by Arthur Machen 6/10

Shudders, Cynthia Asquith, ed., 1929

A young man rents a cosy room in a small English town, having fled Ledham after committing murder. He plans to wait for things to cool off then take the train to South London where he would find work and disappear in the crowd. But as he waits, his mind plays tricks on him. An interesting psychological suspense story, well written, but lacking a strong finale.

The Little People by Robert E. Howard 4/10

Coven, 13 January 1970

An American brother and sister are visiting the English moors, and the older brother explains to his sister that the "little people" stories of Arthur Machen are based on tribes that existed a long time ago. To prove that the idea of little people is "rot," sister Joan decides to spend the night out on the moors. Then the expected happens. Really not very good, and not surprising that it remaining unpublished during Howard's lifetime (1906 - 1936). Like the Stoker story included in this anthology, it was resurrected in order to give hungry readers something new.

Scar Tissue by Henry S. Whitehead 6/10

West India Lights, Arkham House, 1946

Our narrator Gerald Canevin takes in a young man named Joe Smith, who has "ancestral memories," memories of former lives. Smith proceeds to tell of his memories fighting in an arena, and provides proof via a scar left from what should have been a fatal wound.

Surprisingly interesting. I enjoyed the arena re-telling, whereas high adventure normally bores me, and I feel overall the idea is well presented, with no real resolution. But I suppose that scar tissue points to the truth in that final scene.

The Hero of the Plague by W. C. Morrow 7/10

The Californian, January 1880, as "The Man from Georgia"

A disheveled yet honest-looking man named Baker appears one day at a hotel, asking for work. Though ridiculed by the porter, the sympathetic hotel owner takes him in. A victim of wrongful imprisonment, Baker is distracted and confused, but recovers over time with the comforts of the hotel. One day a guest infected with cholera dies at the hotel, and the doctor, with the help of the owner and Baker, administer to the sick.

This is a well written story with some fine dialogue that borders on the comically ludicrous, a style I quite enjoy. There is predictability and pathos, but Baker is well drawn and I very much enjoyed reading this. I much prefer the more appropriate original title, "The Man from Georgia," as the title used for the anthology covers only a minor portion of the tale, and sucks the pathos marrow.

The Horror Undying by Manly Wade Wellman 7/10

Weird Tales, May 1936

Lost in the woods in the middle of a snowstorm, a man takes shelter in an abandoned cabin, and finds under the floorboards a documents that tell stories of what appear to be cannibalism.

Though predictable through and through, the tales within the pamphlets and clippings are interesting and engaging. We are expected, however, to believe that the narrator, who reads and then destroys the documents, is able to quote their entirety verbatim.

The Machine that Changed History by Robert Bloch 7/10

Science Fiction Stories, July 1943

Hitler's scientists have constructed a time machine, and Hitler has Napoleon brought from 1807 to present day 1942. Hitler hopes that the brilliant strategist can help undo his errors and bring him world domination, promising to share the spoils with Napoleon. But Hitler does not count on this story being written by a young Robert Bloch, so there is a twist on its way.

The Candle by Ray Bradbury 6/10

Weird Tales, November 1942

Unhappily married Jules Marcott spots a decorative candle amid the weapons in an old shop, and instinctively decides to purchase the item. The shop proprietor tells Jules that if he lights the candle and whispers the name of a person, that person will immediately die, and demonstrates this on a frisky cat. The price to rent the candle is three thousand dollars. Desperate and yet without money, Jules steals the candle to seek revenge on the man who stole his wife away.

Predictable, but a fun early Bradbury read.

Unholy Hybrid by William Bankier 6/10

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, September 1963

Sutter Clay is an excellent gardener, able to grow the best stock in the region, and able also to create some exceptional hybrids. When he murders the woman who has spent the winter with him, he buries her amid the pumpkins on his land. A good read but the ending could have been so much more effective, as it delivers the expected rather than offering up somtehing different, or a twist on the expected.

Ten Minutes on a June Morning by Francis Clifford 7/10

Argosy (UK), April 1970

Revolutionary Manuel Suredez, sentenced to death, is reprieved while on the scaffold with the noose around his neck. The Colonel tells him that he was saved because of his excellent marksmanship, and because of this skill he will be sent to the town of Villanova to murder a man. If he fails, his parents and sister will be killed. The man he must assassinate is the personal envoy to the President of the United States.

A surprisingly good story, with a great deal of suspense. Clifford is patient with his story, focusing on its details, and delivers a genuinely tragic end. Francis Clifford was born Arthur Leonard Bell Thompson (1917 - 1975).

They're Playing Our Song by Harry Harrison 5/10

Fantastic Stories of Imagination, December 1964

A very short story about a rock quartet, The Spiders, their obsessive fans and an expected twist.